February 25, 2017

by Samantha Yost

Superstorm Sandy, Credit: Wally Gobetz

In 2012, Superstorm Sandy was a wake-up call to New York City, signaling that the demands of a changing climate are the “new normal,” and the city needs all hands on deck to mitigate the damage of future storms. Although much of the damage caused by flooding events occur during storms, sea level rise is very much a wildcard; higher water levels stack with coastal flooding, increasing the amount of damage that may result.

How much sea level rise can we expect in the next century?

Nobody can say for certain how much global sea level rise we can expect in the next century. Changing sea levels are caused by two main factors: the melting of continental glaciers (most significantly in Greenland and Antarctica), and thermal expansion. Warmer objects expand, and a warmer climate means that our oceans will physically expand in size.

Additionally, the polar regions contain unique “feedback loops.” White colors reflect radiation and darker colors absorb it, so as white ice melts and is replaced by blue ocean water, the area absorbs more radiation and melting increases, which in turn increases the amount of dark area, and so on. The Arctic permafrost also contains enormous carbon and methane sinks in the soil, which are thawed and released as the climate warms, leading to more warming, which thaws more permafrost.

Greenland alone contains enough ice to raise the global sea level by 6 meters (20 feet) if it melted entirely. Antarctica contains enough to raise the global sea level by a staggering 60 meters (200 feet). Although this is the “nightmare” scenario,

research suggests that it’s entirely possible with 11°C of global warming – a likely scenario if we burn all of our proven fossil fuel reserves.

Mainstream models however estimate that by the end of the century, sea level rise will increase by 18cm–59cm (7.1”–23”), with some suggesting as much as 1.4m–1.9m (4.5’–6.25’). Because these trends will be so difficult to reverse , 2100 is only the beginning of the curve. Some studies predict as much as 15m (49”) of increase by the year 2500, at which point New York City would be nothing more than an archipelago.

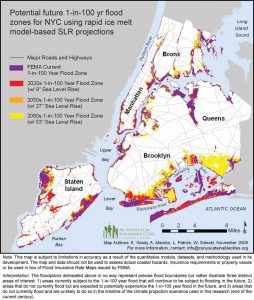

Less than a meter in our lifetimes may not sound like much, but a quick look at flood maps of the city suggests this will greatly increase the number of people and buildings at risk during storms. In the map below, purple represents the area currently in danger of a 1-in-100 year flood event and the increased risk from sea level rise. (For reference, Superstorm Sandy was considered a

1-in-700 year storm event and damaged many areas that had not been deemed at risk from coastal flooding.)

Figure 1 : NPCC, 2010

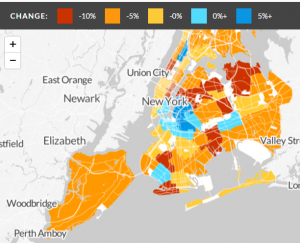

When combined with an income map of the city, it’s apparent that most of the newly-affected areas are lower-income, mostly notably along the Jamaica Bay, the east and west sides of Staten Island, Long Island City, and the Bronx.

Figure 2: Median Household Incomes, WNYC Data News Team

This has broad implications for the city. Most notably, those most at risk of sea level rise are those who are least able to afford to retrofit or purchase flood insurance for their properties.

Attempts to correct for sea level rise can backfire, a fact New York City found out the hard way when FEMA recently tried to update its Flood Insurance Rate Maps for the city. This put thousands of building owners into flood zones where there weren’t any before or upgraded the risk factor of those already in flood zones, forcing them to purchase extremely costly insurance, or increasing the premiums of existing policyholders. A compromise has

since been reached, but the city found itself in the awkward position of trying to take the increased risk of flooding seriously, but also needing to alleviate the economic impact of insurance burdens on already vulnerable communities.

What is the City Doing?

New York City has long realized that it’s in danger from rising sea levels, even before Superstorm Sandy, caused $65 billion in damage and destroyed or damaged 650,000 homes. In 2007, the city commissioned the

New York State Sea Level Rise Task Force to offer science-based solutions and recommendations to the legislature. In 2011, one year before Sandy, the Department of City Planning released the

Vision 2020 Comprehensive Waterfront plan for the future of the city’s 520-mile shore. This plan called for building more public spaces to serve as engineered buffers against coastal flooding.

In 2014, two years after Sandy, Governor Cuomo signed the

Community Risk and Resilience Act, which introduced a further regulatory framework to mitigate sea level rise, and established the

Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency (ORR). Most recently, the city’s ambitious

OneNYC plan lays out what the city intends to do in the next few years to invest in building stock, infrastructure, and coastal defenses.

In addition to fortifying its shoreline, the city is actively working to better manage stormwater within the city. This will help to reduce effluent from

Combined Sewage Overflows (CSOs) into city waterways and protect buildings not in the floodplain from water damage. The city is accomplishing this through the construction of bioswales and natural barriers and sumps that can slow the runoff of surface water during heavy rains.

What Still Needs to be Done?

Although it can be difficult with current regulations, the trick is never to let a crisis go to waste by rebuilding the same way. An excellent example is Battery Park, which was devastated after Sandy and

later redesigned with a host of clever hidden-from-view resilience features to protect against future storms. Buildings that had below-grade mechanical systems destroyed may take the opportunity to relocate those assets to the roof when they rebuild. Resilience professionals sometimes refer to “

bouncing forward” from a crisis, rather than simply “bouncing back.”

The city must continue working to clear away regulatory roadblocks to recovery and resilience, such as changing building codes and working with insurance providers to allow for the deployment of effective floodproofing strategies and allow for strategies such as backwater preventers, dry floodproofing (barricading entrance points from floodwater) and constructing flood barriers. After Sandy, the city’s Build it Back program was plagued with bureaucratic inefficiencies and waste, resulting in some homeowners not having their properties repaired for up to three years. It was a teachable moment for the city to reconsider how it will conduct recovery programs when the next storm hits.

The city must also continue its work to decentralize the power grid, especially by promoting the adoption of solar installations and “islandable” power. The new NYC energy code requires most new residential properties to be “solar ready,” so increasing the stringency of future energy codes; allowing for use of the newest, most efficient

battery storage systems; and encouraging

community solar programs will continue to drive solar adoption.

Most importantly, the city needs to continue having conversations and training events for contractors, developers, and community organizations about the importance of resilience. It takes a great deal of effort to overcome years of “this is how it’s done” inertia when it comes to designing buildings. The city can distribute resiliency plans, but it will make no difference if development professionals do not change the way they build and maintain their properties. There are several organizations attempting to bridge this gap between the government and the general population. Notably,

Enterprise Community Partners has developed a

suite of easy-to-use tools for property owners and developers.

Nobody truly knows what the future will hold for New York City throughout the next century and beyond. Although the city is doing much to mitigate the worst effects of climate change and sea level rise, there is still much that needs to be done to ensure that future generations of residents can enjoy the same safety and security that we have enjoyed. Progress won’t happen alone; it will—quite literally—take a sea change to ensure that New York City’s future is a bright one.